The Maltese Government has a plan for economic recovery. But not all is ship-shape according to economics professor Edward Scicluna.

The Maltese government has only just recently published a financial and economic report that was delivered to the EU’s Economic and Financial Ministers Council. Forewarned of the bloated budgetary deficit and its high rate of public debt, this is the first tweak by the European Commission for the Maltese government.

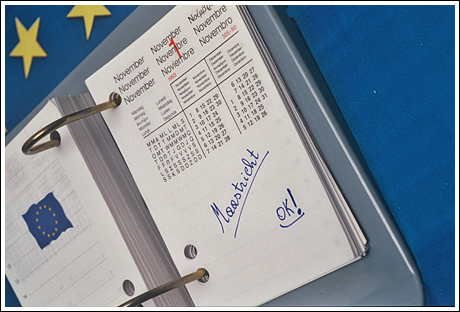

The report is an accounting exercise of how we mean to go from here till 2007, an estimation of figures needed to take us this side of Maastricht acceptability – to a deficit that is lower than three per cent of the GDP, and government debt whose ratio to GDP must not exceed 60 per cent, and with inflation and interest rates not departing significantly from the EU average.

It’s a tall order. The Maltese economy is heaving under a top-heavy civil service, a disheartening restructuring process which has to be carried through, and a divestiture of the country’s most sacred public corporations. At the same time, the Nationalist government is eager to join the Exchange Rate Mechanism II of the Euro as soon as possible, that is, the two-year waiting room for all aspiring Euro adherents.

Prof Edward Scicluna is invited in for a cursory look at the report, which in turn is one of a kind since it exposes the need to have Government provide an up-to-date check on the progress of the economy to the European Commission and ECOFIN, and so hopefully the report remains free of any political meandering.

According to the OPM, the plan had been discussed with the Malta Council of Economic and Social Development towards the end of 2003, which culminated in Budget 2004. The plan should reflect the substance of the MCESD discussions. The GWU however, has requested an urgent meeting of the Council to discuss the document and its implications Scicluna, former chairman of the MCESD until November 2003, says it is an important document:

“It is important because as new EU members, government is intent on joining the European Monetary Union. Joining the EMU is normally a political decision. Going by the Central Bank’s governor’s speech last December, it looks as if the Central Bank is eager to join the Euro as soon as possible, and is advising the Government accordingly. “The UK has taken a different line of reasoning, with the decision to be taken fully by the Blair government and not by the Bank of England. One needs to recall what Commissioner Fritz Bolkestein said: he told the Maltese that whilst joining the Euro is politically attractive, this is a one time major decision, which would close any window of opportunity if the economic need for one were to arise. The fact is that a small economy like ours has never been tested in these uncharted waters. One cannot say that our economy has truly achieved full liberalisation yet.” Scicluna believes that before the decisive moment comes, it should be preceded by a period of preparation for the stringent reality of the Euro.

Scicluna leafs through the pages of the Convergence Report, but expresses reservations: “I would have liked Government to first take the bull by the horns: Once you come up with the decisions with regards to pensions, health reform and public expenditure, you then present the figures. As it is, all these indicators are reflecting the still unsolved structural problems, which the government is now committed to deal with.” According to Scicluna, in the circumstances, what you finish with is a technician’s report, juggling numbers by working backwards from a desired goal. In layman’s terms, the report makes government look like it is working its way backwards slowly from its desired destination, fitting in the milestones as best as it can.

“Political direction cannot be taken by a bureaucrat or an economist, so what does this report mean? Unfortunately, this report was prepared at a time when the Prime Minister was finding his feet as finance minister. I’d rather have the government’s vision on policies translated into figures rather than the other way round. You can tell that this report lacks that political vision.”

Scicluna lets out a disdainful moan at the fact that Quality Service Charters still figure as an instrument of institutional reform: “Here is an example of the tail wagging the dog, the real administrative reforms which have to take place. When we come to the section on administrative reforms we find, for example, private-public partnerships which ‘are being considered.’ What are we talking about? Where, how? A good model to follow is the old peoples’ homes, but where are the others?

“Another section is the White Paper on the Civil Service, a paper written by civil servants for civil servants. You know it takes a brave surgeon to undertake surgery on himself. You need outsiders who have to be very clinical and lay down the line on the reforms needed.

“Quality Service Charters are old hat; very little to do with productivity. Of course you would expect courteous secretaries, but shouldn’t we be talking about good value for money and drastic cuts in expenditure? We have to find other solutions.” Scicluna considers future revisions to the document. He is convinced that once government gets on top of the problems, it can realise what is really needed. The deadline imposed by the Commission must not have helped, hence the need for technicians to come in and fit in the figures nicely, and draw up the report as quickly as possible. The unfavourable international economic situation is no longer a palatable excuse, Scicluna argues. Emerging economies all over the world, the closest to home being Eastern European nations, are reporting economic growth at the rate of five and six per cent. Malta envisages a growth of two per cent: indeed, a bleak future which, Scicluna says, allows no space for an increase of jobs in the number required, and also throwing away the chances of ever converging with the EU average standard of living.

In fact, the ultimate aim of the Maastricht criteria is that through deficit-reduction, the cuts in expenditure should release so many previously underutilised resources into the private productive sector, for the creation of more employment. Otherwise, on its own, deficit reduction with its implied expenditure cuts would be very deflationary with less money going into the economy.

The idea however would be a decisive expenditure cut, but at the same releasing the supply-side push needed to incentivise the private sector. “It’s a tricky situation; it requires a balance between a smaller government and increasing private activity,” Scicluna says.

The other bête noire plaguing the economy is of course pensions, which is unfortunately locked within the political tribulations between the PN and the MLP. For Alfred Sant, the pensions crisis that is sounding the alarms is in fact no crisis. Asked for his views, Scicluna is quite emphatic: “Any claim as to the sustainability or otherwise of any pension plan must come up with support of relevant figures with models detailing the next fifty years.

“After all what did the World Bank report show? It showed that Government’s own plan, no matter how elaborate and mathematical, was also not sustainable for the period following the next 15 years.”

At the time of Scicluna’s chairmanship of the MCESD, the debate on pensions had still been in the remit of the Welfare Reform Committee, although since then the WRC has started working with the MCESD, now that the government is preparing a White Paper on the issue.

“The actual concern is for young people. They should come to the debate and see what the future has in store for them and see for themselves what this will be like. It looks as if it is today’s pensioners’ problem, but in reality it isn’t. In the future, there won’t be enough people to support the pensioners then. It will never be as good as today.” Labour often criticised the MCESD as a smokescreen for the government. Scicluna’s experience is that the council is as good as the people in it, and as good as the preparatory work that is done. “If you talk about a health scheme, you can’t just reform it on a couple of on-the-back-of-the-envelope calculations. You get countries like Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Hungary and others where, their universities, research institutes, and Academy of Sciences are rich with papers, studies, and reports on subjects which their politicians are asked to make policy. This, unfortunately for our policy makers, does not happen here.”

When Scicluna was about to leave his position as chairman of the MCESD, the social partners were warming up to the idea of drawing up a social pact: “Once all the partners commit themselves to the social pact, it would be ideal for everyone to submit their studies and proposals.

“You would expect everyone to look at the national interest from their subjective point of view, so there’s no one pact. There would be some four or five contributions which would be integrated into one. The social pact means agreement, and that means there is a need of communication between government, the unions and the employers. “There is a limit to how much one can do. It is in fact not an easy thing to do. There are many issues to deal with it.

“Just last week, the biggest union in Hungary drew up a pact with the government, saying it would keep wages in line with the GDP growth, whilst the government would promise to aspire for an acceptable growth rate. The fact is the Maltese unions lack information. How many times have we been saying that wages should not outstrip productivity growth? Where are the published statistics of productivity measures? “Suddenly, we open up this Convergence Report and we find that labour productivity in 2003 registered a decline from 2.3 per cent recorded in 2002 to –0.9 per cent in 2003. If it were publicly known before Government itself could have used this fact as a bargaining chip with the civil service.”

Scicluna points out some of the graver statements in the report. The report itself states the economy is predicted to operate below its potential during the forecast period, that is up to 2007. Our vision, on the contrary, should be that by increasing our competitiveness increased foreign demand for Malta’s goods and services would take the economy to its full potential, while the supply side of the economy through higher labour force participation and increased FDI would further increase Malta’s own economic potential. This is exactly what Ireland succeeded in doing, and that is what the document should have strived to achieve. Our aspirations would not accept anything short of that. But that message has to come from the politician and not from a bureaucrat.

“In another section, the report states the Maltese economy was operating above its potential between 1995 and 2002. Now who would believe that? For goodness’ sake… Just because a junior economist chooses one controversial method of measuring potential output using very arbitrary parameters, one must be careful before one includes that technique in such an important document, without some calibration with other methods.

“The same can be said when the document comes to talk about growth. The report merely talks about the growth of exports by 1.3 per cent in 2004 and three per cent after that, fuelled by the growth in world demand.

“What about our competitiveness. Why does it not feature in this context. Competitiveness must be the real target which Malta has to achieve, instead of just banking on the international economic situation.”

153 responses to “Journeying to Maastricht”

alo 789 dang nh?p: alo789 – alo789hk

mexican pharmacy online store: Mexican Pharm International – mexican pharmacy online store

https://mexicanpharminter.com/# mexican pharmacy online store

http://interpharmonline.com/# best rated canadian pharmacy

pet meds without vet prescription canada

MexicanPharmInter: reliable mexican pharmacies – mexican drug stores online

canadian mail order pharmacy: Pharmacies in Canada that ship to the US – best canadian online pharmacy

https://interpharmonline.shop/# canadian pharmacy ltd

maple leaf pharmacy in canada

canadian mail order pharmacy: canadian drugstore online no prescription – legit canadian pharmacy

reliable mexican pharmacies buying from online mexican pharmacy mexican drug stores online

https://generic100mgeasy.com/# Generic 100mg Easy

kamagra kopen nederland: kamagra 100mg kopen – Kamagra Kopen

Officiele Kamagra van Nederland Kamagra Kopen Online kamagra kopen nederland

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# kamagra jelly kopen

Generic100mgEasy: sildenafil over the counter – Generic 100mg Easy

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# kamagra jelly kopen

buy generic 100mg viagra online Generic 100mg Easy Cheap Viagra 100mg

Generic 100mg Easy: sildenafil 50 mg price – Generic100mgEasy

https://tadalafileasybuy.com/# Tadalafil Easy Buy

KamagraKopen.pro: kamagra jelly kopen – Kamagra Kopen Online

kamagra jelly kopen kamagra pillen kopen kamagra pillen kopen

http://generic100mgeasy.com/# Generic 100mg Easy

Tadalafil Easy Buy: Tadalafil Easy Buy – Tadalafil Easy Buy

https://generic100mgeasy.shop/# Generic 100mg Easy

buy generic 100mg viagra online: Generic 100mg Easy – buy generic 100mg viagra online

kamagra pillen kopen kamagra gel kopen kamagra jelly kopen

https://generic100mgeasy.shop/# buy generic 100mg viagra online

п»їcialis generic: Cheap Cialis – Buy Tadalafil 10mg

TadalafilEasyBuy.com: cialis without a doctor prescription – cialis without a doctor prescription

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# KamagraKopen.pro

Viagra online price buy generic 100mg viagra online generic sildenafil

Kamagra Kopen Online: Kamagra – Kamagra Kopen Online

https://generic100mgeasy.com/# Cheap Sildenafil 100mg

Kamagra: Kamagra Kopen – kamagra 100mg kopen

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# kamagra kopen nederland

Generic 100mg Easy: Viagra online price – sildenafil 50 mg price

пин ап вход – пин ап

Generic 100mg Easy Generic 100mg Easy Generic100mgEasy

пин ап – пин ап вход

пин ап – пин ап зеркало

kamagra jelly kopen Kamagra KamagraKopen.pro

pinup 2025 – пин ап казино

пин ап вход – pinup 2025

Generic100mgEasy Generic100mgEasy Generic100mgEasy

пин ап казино официальный сайт – пин ап

пин ап – пин ап зеркало

пин ап казино официальный сайт – пин ап вход

Apotheek Max ApotheekMax de online drogist kortingscode

Kamagra online bestellen: Kamagra online bestellen – Kamagra online bestellen

Kamagra Original: Kamagra kaufen – Kamagra online bestellen

http://apotheekmax.com/# Betrouwbare online apotheek zonder recept

online apotheek ApotheekMax online apotheek

Online apotheek Nederland zonder recept: Betrouwbare online apotheek zonder recept – Beste online drogist

http://apotheekmax.com/# Apotheek Max

Kamagra kaufen ohne Rezept: Kamagra Original – kamagra

https://kamagrapotenzmittel.com/# Kamagra Original

Apotheek Max: Beste online drogist – Online apotheek Nederland zonder recept

http://apotheekmax.com/# Beste online drogist

Kamagra kaufen ohne Rezept Kamagra kaufen ohne Rezept Kamagra Original

kamagra: Kamagra Oral Jelly – kamagra

https://apotekonlinerecept.shop/# apotek online recept

http://apotekonlinerecept.com/# Apotek hemleverans recept

ApotheekMax: online apotheek – Apotheek Max

de online drogist kortingscode Beste online drogist online apotheek

http://kamagrapotenzmittel.com/# kamagra

https://kamagrapotenzmittel.com/# Kamagra Oral Jelly kaufen

Kamagra kaufen: Kamagra online bestellen – Kamagra Original

Apotek hemleverans idag: Apotek hemleverans recept – Apoteket online

https://apotheekmax.shop/# Online apotheek Nederland zonder recept

https://apotekonlinerecept.com/# apotek online recept

kamagra: Kamagra Oral Jelly kaufen – Kamagra Gel

kamagra Kamagra Oral Jelly kaufen kamagra

https://apotekonlinerecept.shop/# apotek online recept

Apotheek Max: de online drogist kortingscode – Online apotheek Nederland zonder recept

canadian online pharmacy: GoCanadaPharm – thecanadianpharmacy

buy prescription drugs from india top 10 pharmacies in india п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

https://wwwindiapharm.shop/# buy medicines online in india

www india pharm: www india pharm – www india pharm

https://wwwindiapharm.shop/# indian pharmacy paypal

reputable canadian online pharmacy go canada pharm canadian pharmacy 24

canadian pharmacy world: canada pharmacy 24h – canadian pharmacy 1 internet online drugstore

http://wwwindiapharm.com/# Online medicine home delivery

www india pharm: www india pharm – top online pharmacy india

purple pharmacy mexico price list Agb Mexico Pharm reputable mexican pharmacies online

https://wwwindiapharm.com/# www india pharm

canada ed drugs: go canada pharm – canadian discount pharmacy

online canadian pharmacy reviews: reputable canadian online pharmacy – canadian pharmacy no rx needed

https://agbmexicopharm.shop/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

www india pharm: www india pharm – www india pharm

www india pharm: www india pharm – buy medicines online in india

http://wwwindiapharm.com/# top 10 pharmacies in india

indian pharmacy: top online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy

canadian discount pharmacy: GoCanadaPharm – legit canadian online pharmacy

https://gocanadapharm.com/# canada ed drugs

www india pharm world pharmacy india www india pharm

legitimate canadian online pharmacies: go canada pharm – recommended canadian pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – Agb Mexico Pharm

canadian drugstore online vipps canadian pharmacy reputable canadian online pharmacy

http://wwwindiapharm.com/# world pharmacy india

www india pharm: www india pharm – world pharmacy india

AmOnlinePharm: buy amoxicillin 500mg canada – amoxicillin 500 capsule

https://lisinexpress.shop/# Lisin Express

generic lisinopril 3973 Lisin Express Lisin Express

ZithPharmOnline: zithromax cost australia – zithromax 250

https://clomfastpharm.com/# Clom Fast Pharm

http://predpharmnet.com/# Pred Pharm Net

Lisin Express: Lisin Express – prinivil 20mg tabs

http://clomfastpharm.com/# Clom Fast Pharm

amoxicillin medicine over the counter: amoxicillin 500 mg price – amoxicillin no prescription

india buy prednisone online Pred Pharm Net Pred Pharm Net

https://predpharmnet.shop/# Pred Pharm Net

lisinopril pill: zestril 10 mg cost – zestril 20 mg price canadian pharmacy

amoxicillin generic: amoxicillin 500mg cost – AmOnlinePharm

https://clomfastpharm.shop/# Clom Fast Pharm

buy prednisone 10mg Pred Pharm Net buying prednisone on line

Lisin Express: lisinopril medication – Lisin Express

https://predpharmnet.shop/# Pred Pharm Net

buy prednisone 5mg canada: Pred Pharm Net – prednisone for sale

https://clomfastpharm.shop/# how to get generic clomid

generic clomid price: how can i get cheap clomid without a prescription – get generic clomid now

AmOnlinePharm: how to get amoxicillin over the counter – amoxicillin brand name

http://zithpharmonline.com/# zithromax capsules price

Clom Fast Pharm: Clom Fast Pharm – get generic clomid without rx

http://amonlinepharm.com/# amoxicillin 500mg capsule

Clom Fast Pharm: Clom Fast Pharm – cost generic clomid pill

gГјvenilir bahis siteleri 2025 casibom giris casino maxi casibom1st.shop

http://casibom1st.com/# superbetin giriЕџ

sweet bonanza 1st: sweet bonanza oyna – sweet bonanza giris sweetbonanza1st.shop

sweet bonanza 1st: sweet bonanza slot – sweet bonanza 1st sweetbonanza1st.shop

http://sweetbonanza1st.com/# sweet bonanza slot

en iyi bahis sitesi hangisi: casibom mobil giris – casino Еџans oyunlarД± casibom1st.com

sweet bonanza giris: sweet bonanza siteleri – sweet bonanza yorumlar sweetbonanza1st.shop

sweet bonanza demo sweet bonanza siteleri sweet bonanza 1st sweetbonanza1st.com

en iyi deneme bonusu veren siteler: casibom – casД±no casibom1st.com

rcasino: casibom guncel giris – en Г§ok freespin veren slot 2025 casibom1st.com

sweet bonanza 1st sweet bonanza slot sweet bonanza yorumlar sweetbonanza1st.com

casino siteleri 2025: slot casino siteleri – slot casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.com

gГјvenli siteler: casibom mobil giris – welches online casino casibom1st.com

casinombet: casibom giris – sГјpernetin casibom1st.com

https://casinositeleri1st.com/# guvenilir casino siteleri

bet siteleri bonus: casibom giris adresi – casinomaxi casibom1st.com

casino siteleri casino siteleri lisansl? casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.shop

http://sweetbonanza1st.com/# sweet bonanza demo

casino siteleri 2025: lisansl? casino siteleri – deneme bonusu veren siteler casinositeleri1st.com

casino siteleri: guvenilir casino siteleri – vidobet giriЕџ 2025 casinositeleri1st.com

slot casino siteleri guvenilir casino siteleri by casino casinositeleri1st.shop

https://usmexpharm.shop/# UsMex Pharm

USMexPharm: mexican pharmacy – п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

https://usmexpharm.shop/# UsMex Pharm

mexican pharmacy: UsMex Pharm – Mexican pharmacy ship to USA

usa mexico pharmacy: Mexican pharmacy ship to USA – mexican pharmacy

https://usmexpharm.com/# mexican pharmacy

certified Mexican pharmacy Mexican pharmacy ship to USA UsMex Pharm

https://usmexpharm.shop/# certified Mexican pharmacy