European labour markets are generally considered to be too rigid. Making labour market rules more flexible while at the same time providing a good level of social protection is one of the main challenges of the EU’s strategy for economic, social and environmental reform (the ‘Lisbon Agenda’).

- Source: http://www.euractiv.com

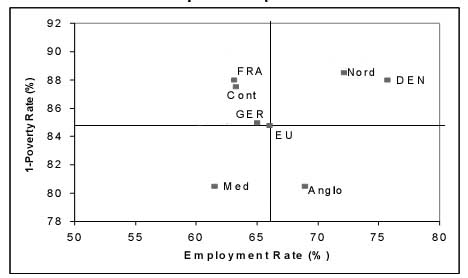

In a reportfor the European Commission, economist André Sapir of the Bruegel think tank classified European social models into four groups:

- The Mediterranean model (Italy, Spain, Greece): Social spending concentrated on old-age pensions and a focus on employment protection and early retirement schemes – inefficient both in creating employment and in combating poverty.

- The Continental model (France, Germany, Luxembourg): insurance-based, non-employment benefits and old-age pensions and a high degree of employment protection – good at combating poverty but bad at creating jobs.

- The Anglo-Saxon model (Ireland, the UK and Portugal): Many low-paid jobs, payments linked to regular employment, activating measures and a low degree of job security – relatively efficient at creating employment but bad at preventing poverty.

- The Nordic model (Denmark, Finland and Sweden, plus the Netherlands and Austria): High spending on social security and high taxes, little job protection but high employment security – successful at both creating jobs and preventing poverty.

Employment Rates and Probability of Escaping Poverty in European Social Systems:

FRA=France; GER=Germany; DEN=Denmark; EU=EU average; Cont=average of continental systems (BE, DE, FR, LU); Nord=average of Nordic systems (AU, DK, FI, NL, SV); Med=average of Mediterranean systems (HE, IT, ES); Anglo= average of Anglo-saxon systems (IR, PT, UK)

Source: André Sapir / BRUEGEL; edited by EurActiv

The secret behind the success of the Nordic models was found to be the ‘flexicurity’ approach, which was implemented in Denmark in the early 1990s, and – with some variations – in other Nordic countries, the Netherlands and Austria. The approach is based on social dialogue between employers’ organisations and trade unions, and it was initially promoted by Social Democratic politicians such as Poul Nyrup Rasmussen, who was Danish prime minister from 1992 until 2001.

The concept rests on the assumption that flexibility and security are not contradictory, but complementary and even mutually supportive. It couples a low level of protection for workers against dismissals with high unemployment benefits and a labour market policy based on the obligation and right of the unemployed to receive training. The concept of job security is replaced with employment security.

Issues:

Much of the discussion since the publication of the Sapir report has focused on features of the more successful economies – namely the Nordic ones – which could be applied to those lagging behind. In particular, the systems of Germany and France, which used to be the motors of the EU economy, have found themselves under scrutiny.

In Sapir’s presentation, France and Germany are in the ‘continental’ sector. Both countries’ social systems are characterised by a relatively high degree of employment protection: businesses argue this makes it tough for them to hire people, as they would then have difficulties firing them again.

Average tenure in years with the same employer

| Denmark | Germany | France | |||

| 1992 | 2000 | 1992 | 2000 | 1992 | 2000 |

| 8.8 | 8.3 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 11.2 |

Source: http://www.socsci.auc.dk/carma/carma-1.pdf

Original flexicurity concepts in the Nordic countries arose from work relations and the acceptance of taxation and trade unions, issues which date back to the early years of the 20th century. It has thus been argued that they cannot simply be transplanted into other countries.

When the Commission drafted its Communication ‘Towards Common Principles of Flexicurity: More and better jobs through flexibility and security’ (published on 27 June 2007), it was aware of this dilemma. It limited itself, therefore, to defining somecomponents of successful flexicurity policies, which can be incorporated into any country’s labour-market policies without altering the concept’s underlying principles, namely:

- Flexible and reliable contractual agreements;

- comprehensive lifelong learning;

- effective active labour market policies, and;

- modern social-security systems.

The Commisison paper then tackled the difficult task of making suggestions on how to proceed with labour-market reforms. In order to avoid giving specific advice to member states, it defined a typology of four different challenges that labour markets in different countries may be facing, leaving governments to assess which of the recommendations apply to them.

For each of the situations, the authors suggested a ‘pathway’ out of the respective labour-policy impasses, touching on each of the four elements of flexicurity. The typology comprised the following situations:

- Key challenge: Contractual segmentation. The labour market is divided between ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’, or workers holding permanent contracts and those on short-term contracts with low levels of social protection. Typically, these countries are marked by a high rate of early retirement. Examples include Spain, Italy, France and Portugal.

Suggestion: Aim towards a more even distribution of flexicurity and security to create ‘entry points into employment’ for newcomers and promote their progress into better contractual agreements. - Key challenge: Developing flexicurity within the enterprise and offering transition security. A high percentage of large enterprises leads to low job mobility within the workforce. This is the case in Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg and France.

Suggestion: Invest in employability and life-long learning to increase workers’ adaptability to technological change; provide for better and safer transitions from one company to another. - Key challenge: Skills and opportunity gaps among the working population. In countries with high employment rates, such as the UK, the Netherlands and even Denmark, the cradle of flexicurity, low-skilled groups have little chance of finding a better job than the one that they currently hold.

Suggestion: Promote opportunities and develop the skills of low-skilled workers in order to enable upward social mobility. - Key challenge: Improve opportunities for benefit recipients and informally employed workers. This situation is typically encountered in countries that have joined the EU since 2003 and have undergone intensive restructuring, resulting in a high percentage of the potential workforce being dependent on long-term benefits.

Suggestion: Introduce or reinforce active labour-market policies and life-long learning to improve opportunities for benefit recipients to move from informal to formal employment.

Positions:

In an interview with EurActiv Czech Republic, Employment and Social AffairsCommissioner Vladimír Špidla expressed his conviction that flexicurity is essential to meeting the demands of our changing societies, saying “what we must give people in the first place is not the security of having a single job, but a security of career and especially support during a change”.

However, he warned that this approach is “very complex” and requires “a certain structure” to the education and on-the-job training systems. Moreover, “flexible but at the same time reliable labour law” and “modernisation of social security systems to make them effective” are necessary, he said.

Speaking at Employment Week 2007, the Commissioner Vladimír Špidla said: “I think that the Commission has promoted the debate on flexicurity with its initiative to encourage worker’s mobility and to facilitate transitions from one job to another. Of course, there are no simple answers and no single answers to all the questions that arise. But the objective is to put human capital at the centre of our efforts. This is exactly what the debate on flexicurity is all about.”

BusinessEurope President Ernest-Antoine Seillière said in March 2007 that there was no EU-wide, ‘one-size-fits-all’ model of flexicurity, adding “decisions on concrete measures can only be taken in the member states”. However, he highlighted the useful role that the EU can play in “identifying common principles and pathways in order to facilitate discussions and policy developments at the national level.”

BusinessEurope Secretary-General Philippe de Buck added, speaking in Copenhagen on 31 January 2007 : “Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all model for flexicurity. It is true that flexicurity has its roots in Denmark and has been a success for the Danish labour market. However, implementing flexicurity across the EU is not about exporting the Danish model but exporting its principles and concept. After that, Member States will have to find their own specific flexicurity policies, adapted to their socio-economic situation and institutional framework. In addition, the flexicurity approach must be truly embedded in and considered an integral part of the Lisbon strategy. If it is not accompanied by the necessary reforms (i.e. implement sound budgetary policies, increase investment in R&D and innovation), the flexicurity approach, on its own, will fail to help preserve the European social model and achieve the objectives of more and better jobs and higher productivity.”

Andrea Benassi, Secretary-General with SME federation UEAPME, declared on 1 February 2008: “A fluid and reactive labour market is a key precondition to achieve the Lisbon goals and increase Europe’s competitiveness. Unfortunately, the present situation in Europe is far from being ideal in this respect. Excessively rigid labour laws, the lack of flexible working patterns, the mismatch between available skills and required skills, ill-designed social protection systems pushing people towards undeclared work are all putting a severe strain on SMEs’ economic potential.”

“Unfortunately, too few National Reform Programmes (NRPs) have taken a systematic flexicurity approach on board,” wrote CEEP, an organisation representing enterprises with public participation and enterprises of general economic interest, in a letter to the 2007 Spring Council. “We hope that both the European Social Dialogue and the elaboration of flexicurity pathways will have a positive impact on next year’s NRPs”, CEEP added, hoping that the primary effect would be an increased focus on the “policy priority of improving adaptability of workers, enterprises and services.”

ETUC, the European Trade Union Confederation, fought hard to have the social security dimension of flexicurity emphasized in the Commission’s approach. On 21 January 2008, ETUC declared: “The European trade union movement welcomes the fact that the EU has adopted a more balanced approach to the principle of flexicurity, and recognised the need to offer workers on temporary contracts more security. On the other hand, with regard to social protection, there is an excessive emphasis on avoiding the perceived risk of benefit systems acting as a disincentive to work, coupled with a failure to learn the valuable lesson from a number of the EU’s most successful Member States that generous benefits are a key ingredient in managing structural change and creating an adaptable workforce.”

In an Open Letter to the Socialist Group in the European Parliament, the left-wingGUE/NGL group – also from the Parliament – spoke of increased ‘flexploitation’ of workers in Europe. Despite “a number of improvements” achieved so far in the draft report on flexicurity by the Committee on Employment and Social Affairs, the Open Letter insists that Parliament must put much greater stress on getting the review of the guidelines package focused more on promoting the quality of employment, improving social security and social inclusion, better social risk management and the reconciliation of work and non-work life.

The Social Platform, which brings together Social NGOs from all over Europe, stressed the importance of inclusion and a high level of social security to the flexicurity approach: “In addition to globalisation, technological change and demography the following trends need to be given more attention to enrich the implementation of the European flexicurity principles: rising inequalities, discrimination, migration, public health issues, strengthened role of the third sector, diversity of families and new role for women and men. […] A compulsory and adequate first pillar pension system remains the most efficient way to address flexicurity in relation to frequent job changes, career interruptions and participation in life long learning opportunities while at the same time securing an adequate income in old age.

The European Confederation of Private Employment Agencies (Eurociett) welcomed the Commission’s communication “as it recognises the inherent and positive contribution of temporary work agencies in implementing flexicurity policies”. The asssociation also welcomed the “upcoming debate at European and national level on pathways to implement flexicurity policy approaches in Europe”, adding that “EU member states should explicitly take advantage of the concept of flexicurity in labour market reforms” and “recognise the positive contribution of private employment agencies to flexicurity policies”.